If you’re approaching this topic for the first time – or if you’ve ended up here by mistake – you’re probably wondering: Why train a cat?!

You might have come across incredible stunts, like the one from The Saviktsy Cats, who performed in the 2018 show of America’s Got Talent. But teaching your cat to jump 2 meters high and flip upside down is not why we want to provide you with this cat training guide. (Although that would be pretty cool.)

Instead, we want to help you improve your relationship with your cat as well as his sense of well-being. Through training, you can help him use up some of his energy in a healthy way, stimulate his mind, have fun, and approach some otherwise daunting experiences in a more relaxed way.

Training cats isn’t yet very popular. But just because only a handful of people have thought of training their cats, that doesn’t mean that it’s an impossible or unreasonable task.

Before we dive into training, we need to spend a few paragraphs about actually understanding your cat and the way he thinks.

How cats really perceive the world: their journey from wild to domesticated

Cats have a unique way of perceiving and analyzing the world around them. For example, they don’t digest that people come in different shapes and sizes, that men, women, children, behave and sound differently; that you might want to bring another kitten (or dog) into your home; or that you need to confine them for their own good (e.g. take them to the vet) every so often.

It all comes down to the order in which they process and prioritize the information they receive. And it makes perfect sense once you understand their journey from wild predators to domestic pets.

According to The Trainable Cat by John Bradshaw and Sarah Ellis, ten thousand of years ago there were no domesticated cats in the world: only around 30 species of small wildcats (and, of course, big cats).

All of them – big and small – trace their origins back 10 million years to one single cat, the Pseudalurus.

The first reliable records of domesticated cats come from Egypt, about 6000 years ago. However, the domestication process likely started several years earlier, prompted by a key event in our journey toward civilization: the appearance of the house mouse.

The house mouse is believed to have made its first appearance when humans switched from foraging to cultivating and stockpiling, thus providing a new, endless and vulnerable source of food to pests.

Wildcats started being attracted to villages, where they could find high concentrations of rodents.

For thousand of years, cats would only approach human villages to hunt, and then retreat into the wild. In this unprecedented scenario, however, a few individuals began to stay in the villages in between hunts. Villagers likely provided food and a safe place to sleep and have litters, to encourage them in their rodent hunt and keep their barns pest-free.

The Natufians are believed to be the first civilization to be plagued by rodents (on an area now overlapping Israel, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria) 10,000 years ago – and this is where wildcats most likely started their self-domestication process.

The Trainable Cat, by Brad Shadow and Sarah Ellis

After several generations, wildcats slowly started being more tolerant of people, eventually resulting in what we now know as the domesticated cat.

Why your cat behaves like he does

Learning where cats originate from and what is at the root of their behaviours should help you understand why they do what they do.

For example, why many cats can’t tolerate other cats. Similarly to most modern cat behaviours, this tendency can be traced back to thousands of years ago.

More and more cats became tolerant of humans, but they still couldn’t live side by side with other members of their own species. As wildcats self-domesticated in our ancestors’ villages and territorialism became a problem, they had to spend less time hunting and providing a safe place for their litters, and more time watching their backs against attacks by rivals.

Why does your cat keep hunting and gracing you with his half-dead prays, even if you feed him well? That’s another behaviour that you might find puzzling.

First, take a look at your cat’s anatomy: he’s highly specialized for hunting. His retractable claws can be used only when intended, so they don’t wear down and can be as effective as possible. His ears are enormous compared to his head – and allow him to capture ultrasounds, such as the squeak of a mouse, pinpointing the exact location where it came from. His nose has 200 million odor-sensitive cells; by comparison, we only have 5 million odor-sensitive cells.

Until just a few generations ago, a cat’s ability to hunt was crucial for a his survival. Also, a cat’s prey is generally quite small: a mouse only has about 30 calories, so a cat would have to hunt at least 10 of these a day to survive. If they couldn’t find prey soon enough and waited to hunt until they starved, they would die.

This behaviour is still deeply ingrained in our cats today, and that’s why they will hunt even when they’ve just been fed.

Therefore, a ‘heartless killer’ is simply a cat who’s following a genetic code that has served him well throughout thousands of years, and it would be unfair of us to think they should (or could) just change it at the snap of our fingers.

Most of your cat’s behavior is dictated by instinct and survival. Your kitty will scratch your furniture because, in the wild, he would need to sharpen his claws to be a successful hunter. He wakes up at 3 am with the zoomies because, in the wild, he would be hunting at night.

However, not all hope is lost. You can still aspire to having a sofa that isn’t torn to pieces, and enjoying a decent night sleep.

Your cat’s world vs your world: How your cat sees you

So how does your cat see you and the world around him?

Although cats are believed to comprehend social relationships in a more sophisticated way than other mammals can, that’s still simpler compared to the way we perceive our relationship with them.

When we talk to our cats, we imagine them listening to us. However, although cats identify us as individuals and react to us, they actually don’t have a clue that we are thinking of them. Cats most definitely don’t see us in the same way that we see them.

Essentially – and this is crucial to cat training – this means they don’t understand our thought process. That’s why trying to scold your cat for peeing outside of his box is completely pointless. He is simply not able to grasp that you are telling him off for an action he performed some time ago.

Cats have excellent memories and association abilities, but they largely live in the present. Their memories resurface when triggered by similar events. They aren’t able to consciously recall memories like we can and, similarly, aren’t able to process the past or the future voluntarily.

Memes about cats plotting to kill you are fun, but the reality is that your cat simply isn’t capable of scheming, plotting or otherwise voluntarily planning any future action.

What we know is that cats have a few ‘simple’ gut feelings, such as frustration, anxiety, happiness and fear, and training works by evoking these feelings through the systems explained below.

The science behind cat training

Cats live “now”, don’t have the ability to feel “guilt” or “revenge” and can’t associate an action they performed with a consequence – if this consequence doesn’t happen exactly at the same time as their action was performed.

A cat will associate the punishment or reward to whatever he’s just done or been thinking about at the time.

Therefore, punishing your cat for something he might have done some time ago is only going to damage his relationship with you – and likely prompt your cat to repeat the same behaviour.

If you’re serious about teaching your cat a new behavior or correcting a bad one, you need work with association learning and positive reinforcement – using the right timing.

We’re about to get a bit technical in the following paragraphs, but – if you really want to understand how your cat thinks, why he does what he does, and how you can change his behaviours – bear with us.

After all the theory, we’ll also give you some practical examples.

Association learning

Research has confirmed that cats are associative learners.

In simple terms, associative learning describes the process in which a new response (or behaviour) is associated with an individual stimulus. Cats develop learning by association by simply carrying on with their daily life and interacting with us, other animals, and their environment. These associations inform them on which behaviours are acceptable, and which aren’t.

Throughout their lifetime, cats are constantly learning – regardless of whether we are teaching them something intentionally or not. Each experience they have, and the consequences of those experiences, are retained in your cat’s memory for later use. These memories will then reliably influence how your cat behaves in the future – and this is where we want to step in with our training.

Navigating consequences

Associative learning will dictate what and how you cat responds to and what to ignore in his daily endeavours.

His learning is often driven by the instinct of survival. If a wild cat expends too much valuable energy to focus on irrelevants detail of their environment, it may impact his survival: like losing track of prey, or being found by a predator.

This is why, throughout his lifetime, your cat will constantly be processing what parts of the environment they should ignore – habituation – and what they should respond to – sensitization.

Sensitization: An increase in a response to a stimulus after repeated presentations. For example, after repeated visits to the vet, your cat becomes more fearful.

Habituation: A decrease in a response to a stimulus after repeated presentations. For example, your cat initially responds strongly to the beep of your microwave. Over time, he learns that there is no negative consequence to the sound, and therefore does not respond to it.

Having a grasp of these terms is important: When you’re training your cat, the consequences of his choices must be consistent and strong enough that your cat does not habituate to them – but they should be reasonable enough that your cat does not become sensitised to them either.

Forms of association learning

There are two main forms of association learning – operant conditioning, and classical conditioning.

In short, whereas classical conditioning depends on developing associations between events, operant conditioning revolves around learning from the consequences of our behaviour.

These learning methods used in cat (and, generally, animal) training work differently depending on the circumstances. Understanding when to use one method over the other is crucial to effectively training your feline friend.

Does this sound complicated? Don’t worry, it’s easier than what these technical terms make it look like. In fact, whether you realise it or not, you already learn by association every single day… and so does your cat.

TIP: The key difference between classical conditioning and operant conditioning is that the first is entirely instinctual and doesn't require any learning, while the latter does. Whereas classical conditioning depends on developing associations between events and therefore happens BEFORE a consequence, operant conditioning involves learning FROM the consequences of our behaviour.

Classical conditioning

The roots of the classical conditioning theory are firmly planted in 18th-century behavioural science.

Classical conditioning is a training method that produces an istinctual, or autonomous, response from your cat. In other words, it simply describes changing your cat’s emotional response to a stimulus.

The term was theorised in 1890s by the Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov, a name you might recognise by his infamous experiment Pavlov’s Dogs.

During his research related to the salivary response in dogs, Pavlov made a startling realisation: it wasn’t just food that triggered salivation. It could be anything related to food, too! He realised this when the dogs began to madly salivate at not only the presentation of their kibble, but by other unrelated stimulus – like the lab assistant who had previously given them their food.

This research was instrumental in the development of behaviour theory, and to a large extent, the way we train animals to this day. Pavlov demonstrated to the world that we could do more than just teach an animal to tolerate certain stimulus – we could actually condition their emotional response to them.

Source: Verywell Mind

Boundless Psychology defines classical conditioning as a type of learning where “a conditioned stimulus becomes associated with an unrelated unconditioned stimulus… in order to produce a behaviour response known as a conditioned response.”

Neutral Stimulus > Unconditioned Stimulus

Which, after repetition, results in:

Conditioned Stimulus > Conditioned Response

In other words, this means that you can train your cat to learn or to become conditioned to a particular sound, smell or behavior associated with the desired response.

While all of this information might sound a little daunting, you will probably start understanding the concept once you get down to the practical training phase. And clicker training is one of the most effective ways to use classical conditioning to train you cat.

Let’s take a look at how clicker training works and why it’s such an effective training method. First, picture this scenario: you have a clicker, a cat (hopefully, yours!) and a bag of treats. Every time you feed your cat a treat, you produce a click sound.

Treat > Click! Treat > Click! Treat > Click!

Neutral Stimulus (Click sound) > Unconditioned Stimulus (Receiving food)

Which, after repetition, results in:

Conditioned Stimulus (Click) > Conditioned Response (“I’m about to receive food!”)

Over time, the clicker stops being just a random sound, and starts being a heavily-loaded stimulus that instantly makes your kitty anticipate treats.

For a full guide on how to click train your cat, click here.

Operant conditioning

The theory of operant conditioning was developed by B.F. Skinner, an American psychologist, in the late 1930s. Skinner had a keen interest in behaviour, and how the behaviour of all species was consistently shaped by the environment around them.

In his research, Skinner uncovered The Law of Effect, a concept that had originally been developed by Edward Thorndike in the late 1800s. According to this principle,

“responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation (Gray, 2011, p. 108–109).”

www.simplypsychology.org

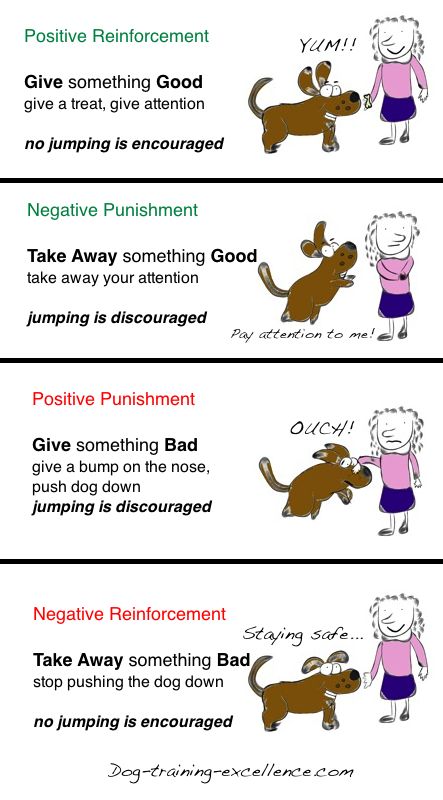

Skinner asserted that animal behavior is shaped by reinforcers: behavior that receives reinforcement is more likely to be repeated, while behavior that doesn’t receive reinforcement is likely to stop occurring. Reinforcements can be divided into four categories:

• Positive reinforcement: increases the frequency of a behavior by giving the subject a wanted reward when the behavior is exhibited.

• Negative reinforcement: increases the frequency of a behavior by removing an adverse stimulus from the individual’s environment.

• Positive punishment: decreases the frequency of a behavior by imposing an adverse stimulus or event in response to the behavior.

• Negative punishment: decreases the frequency of a behavior by removing a stimulus desired by the individual.

Source: www.jrobertbuchanan.com

Positive and negative reinforcement / punishment

You’ve probably encountered the term ‘positive reinforcement’ or ‘negative reinforcement’ before, but it’s very likely you’ve heard them used incorrectly.

Because of its name, negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment. The key difference is that negative reinforcement involves the removal of a negative consequence to increase the likelihood of a response. Reinforcement always increases the occurrence of a response, while punishment always decreases the occurrence of a response.

'Positive and negative' and 'reinforcement and punishment' do not mean good or bad by your standards. Reinforcement means that the behavior will happen more often. Punishment means that the behavior will happen less often.

Source: Dog Training Excellence

How to use classical and operating conditioning to train your cat

If you’ve made it through the theory all the way to this section, congrats! Now it’s time to take the information you’ve learned and use it to train your cat.

To recap: when training your cat, you want to use classical conditioning to istinctively make him associate a sound / visual cue to an action; and operant conditioning to encourage good behavior / discourage bad behavior through positive or negative reinforcement.

Positive punishment is supposed to make a behavior decrease or stop, but you should avoid punishing you cat in any form (yelling, hitting, using a squirt bottle, tossing objects directly at your cat). Cats don’t learn from punishment unless it is applied consistently and immediately – but you won’t be around to watch what he does 24/7. Either way, he will start associating your presence with negative emotions rather than the action or behavior you want to stop. Using punishment is also likely to increase fear and aggression and make the problem worse.

The more often you are able to reinforce a desirable behavior, the more likely the cat will repeat it (think consistency). However, the same is NOT true of using punishment such as a spray bottle. You will not always be around to punish your cat for doing something undesirable, thus, the punishment will not be consistent. And the more consistent you are with punishment, the more frequently your cat is receiving bad juju from you. So, if you are able to be consistent enough with punishment, it comes with a price – fear and distrust.

www.felinebehaviorsolutions.com

Here are a few ideas how you can apply the techniques you just learned in real life:

Discourage bad behavior

Cats respond much better to rewards and positive reinforcement than they do with any form of punishment. However, you can still discourage bad behavior:

- Make a noise: If you see that your cat is about to do something he shouldn’t, make a sudden noise (e.g. shake a can with pennies) to startle him.

- Use harmless deterrents: Use citrus smells and other commercially available odors designed to keep cats from getting to specific areas.

- Use automatic devices, such as an air puffer placed on the area you don’t want your kitty to visit. That way, he will associate the behavior/action with this (harmless and consistent) punishment.

Encourage good behavior

Use rewards and positive reinforcement to make changes to your cat’s behaviors:

- Train your cat to sit: reward longer petting sessions with more treats, and stop the training sessions before your cat has a negative reaction.

- Train your cat to use a scratching pad instead of your furniture: reward him each time he uses it.

- Reward quiet behavior: if your kitty is a loud meower, give him a treat after several seconds of silence if he has been meowing.

Tip: Make sure you are rewarding the correct behavior: wait between the undesirable behavior and the acceptable behavior to help your cat to associate the reward with the correct behavior, or you could be reinforcing the behavior you're trying to stop.

Last training tips

Whether you choose to train your cat by operant or classical conditioning, here are a few tips to make your training sessions as effective as possible:

- Set a goal: what do you want to achieve with this training? Define your goals as clearly as possible – if you’re not confident, your cat will leave your training sessions confused.

- Create the right space: no distractions, loud noises, other animals or people.

- Keep an eye on the watch: keep each session short and natural, about 5-15 minutes per session. Cats quickly lose their interest.

- Prepare your tools: have a bag full of treats, a clicker (if you decide to clicker train your cat) or a stick.

- Start small and be patient: don’t expect to teach your cat to high five in your first training session. Training cats require a lot of patience! Make sure you reward your cat each time he performs an action that progresses toward your desired action or behavior, until he eventually shapes it.

- Don’t punish your cat, use positive reinforcement techniques instead.

That’s it, you’re ready to go! If you don’t know where to begin, we put together a few quick guides:

- How to get your cat tolerate his carrier and enjoy car rides

- How to leash train your cat

- How to teach your cat to come when called

- and How to clicker train your cat.

For more how-to articles, check our Guides section – we update it regularly with new guides.

If you really want to dive deep and train your cat like you could train a dog, understand how they think and perceive us and the world, we highly recommend “The Trainable Cat” by Sarah Ellis and John Bradshaw.

Other books that we recommend for cat training are “The Little Book of Cat Tricks: Easy tricks that will give your pet the spotlight they deserve” and “Trick Training for Cats: Smart fun with the clicker” (for which you’d obviously need a clicker, like this one).

Have you already started practising training your cat? Let us know how it goes in the comments! ?